Réalisation:

Agnès VardaScénario:

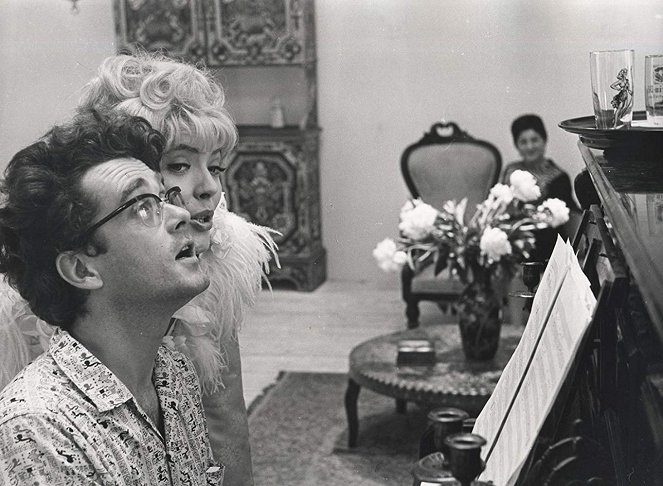

Agnès VardaMusique:

Michel LegrandActeurs·trices:

Corinne Marchand, Michel Legrand, Serge Korber, Jean-Claude Brialy, Sami Frey, José Luis de Vilallonga, Eddie Constantine, Yves Robert (plus)Résumés(1)

Cléo, belle et chanteuse, attend les résultats d'une analyse médicale. De la superstition à la peur, de la rue de Rivoli au Café Le Dôme, de la coquetterie à l'angoisse, de chez elle au Parc Montsouris, Cléo vit quatre-vingt-dix minutes particulières. Son amant, son musicien, une amie puis un soldat lui ouvrent les yeux sur le monde. (Ciné Tamaris)

(plus)Vidéo (1)

Critiques (4)

Cléo de 5 à 7 est pour moi le premier film de la Nouvelle Vague qui m’a ensorcelé du début à la fin. Agnès Varda est parvenue à articuler un scénario de qualité qui, au lieu du papotage philosophique tiré jusqu’à l’absurde (une infirmité classique de la Nouvelle Vague – les intellectuels me pardonneront), reste agréablement terre à terre tout en étant très formel, quand le film se déroule – presque – en temps réel et nous documente une heure et demie critique de la vie de Cléo, la chanteuse titulaire. En fait, ce film de dialogues superbement tourné est un peu le prédécesseur de Before Sunrise, le premier volet de la trilogie de Richard Linklater. Et pour moi, ça s’est traduit par un délicieux moment de quatre-vingt-dix minutes en salle de cinéma alors que j’étais déjà très fatigué après avoir visionné plusieurs projections d'affilée. Malgré la fatigue, avec Cléo de 5 à 7, je n’ai pas pu décoller les yeux une seule minute de l’écran. Et j’aurais pu continuer à le regarder jusqu’à minuit, si pas jusqu’au lendemain. [LFŠ 2019]

()

La nudité est la simplicité. Comme l'amour, la naissance, l'eau. Comme le soleil, la plage, tout cela. Et on pourrait ajouter : comme une vague. Une nouvelle vague. Celle dont la réalisatrice parvient à capturer Paris dans ses multiples reflets, avec sa légèreté et sa simplicité, ainsi que toutes ses rues bondées, ses cafés et ses boutiques. Tout en capturant avec la même légèreté l'intérieur de l'héroïne, dans sa nudité (ceci n'est pas obscène), face à un autre être humain et face à cette même ville. L'égoïsme qui engendre la solitude et l'éloignement des autres, caractérisé par l'utilisation de taxis, est vaincu par le symbole du passage à un bus - où l'héroïne ne peut plus voyager seule. De même, l'échange symbolique d'un coup de téléphone contre une visite personnelle à l'hôpital - regarder son ennemi en face est la base pour le surmonter et prendre la responsabilité de sa propre vie.

()

The anti-Amélie, ungraspable in the manner of the New Wave. Agnès Varda was not a passionate cinephile like the directors from the Cahiers du Cinéma circle. Educated in the arts and humanities, she was less fascinated by cinema than by photography and painting (the paintings of Hans Baldung Grien were a major inspiration for the film’s visual aspect). This is perhaps also a reason that her second feature-length film stands out due to its distinctive grasp of traditional narrative forms (Varda likened her creative process to writing books, calling it “cinécriture”). These forms are neither amplified nor deliberately violated. Instead of adopting or disparaging others’ film language, the director came up with her own way of conveying information to us. Despite her creative grounding in documentary work, this does not involve intuitive directing in the vein of Jean Rouch. Cléo from 5 to 7 has a carefully thought-out concept whose seeming disruption with some unexpected digressions serves the narrative rhythm. ___ The false information about the duration of the protagonist’s odyssey (cinq à sept was an earlier synecdochic term for a visit to a by-the-hour hotel) serves to play a narrative game with two interpretations of time: subjective time and objectively passing time (which is regularly pointed out to us by the clock in the mise-en-scéne). This temporal duality is justified by Varda’s lifelong interest in the relationship between the subjectivity of the individual and the objectivity of the environment, which together shape our identity. She always endeavoured to identify both individual and broader social issues, or rather the common ground between them. ___ With respect to the disregard for standard dramatic structure (exposition, complication, development, climax), the segmentation of the film into thirteen chapters is understandable, as it helps to maintain the brisk pace of the narrative. Three longer intertextual interludes – a radio news report (which also serves to contextualise events in the manner of a documentary), a song and the short slapstick Les fiancés du pont Mac Donald (which is by far the most cinephilic sequence of the film, thanks to the small roles played by Godard, whose beautiful eyes were allegedly the reason that Varda came up with the short, Karina and Brialy) – similarly serve as punctuation marks. The song also bridges the “passive” first half and “active” second haf of the film. ___ Until the singing of the sad song “Sans toi” (written by Michel Legrand), during which the protagonist realises the emptiness of her life and her position as a victim, into which she has been pushed in part by those around her, Cléo is merely an object with a beautiful surface and nothing inside, watched by others and – thanks to the ubiquitous mirrors – contentedly watching herself (a display window full of hats brightens her up the most). The voice, including the inner commentary, belongs to others, as does the centre of the shot, which Cléo only complements with her charm, but she never dominates it. In the second half of the film, she changes from dazzling white to sombre black, takes off her doll-like wig and puts on dark glasses, which enable her to voyeuristically watch others without being watched herself (hiding her eyes makes it impossible for others to ascertain her identity). Later, after removing her glasses, she doesn’t only accept the gaze of others, but also returns it. The camera finally takes her point of view and allows her to see others as objects (the visit to a sculptor’s studio). ___ Cléo starts to stand up for herself. She begins to use her voice and control the fear that has paralysed her. The previous presentiment of death is displaced by a maternal motif (mothers with infants, children on a playground), the idea of life. To put it in feminist terms, the protagonist takes control of her own representation in the second half of the film. She stops giving in to melodramatic passivity and changes the way that she sees herself (while others still see her in the same way, as indicated by the soldier giving her a daisy, a symbol of admiration for feminine beauty). The joyless message at the end of this urban road-movie is ultimately not so devastating due not only to the unspectacular form of its delivery, but mainly due to the paradigm shift. After circling Paris (her route more or less forms a ring), Cléo is no longer an actor in a tragedy to which she can only resign herself. She has found within herself the strength to fight and to take control over which genre her life will belong to. But as the nature of her illness admonishes, this will decidedly not involve full control. 90%

()

(moins)

(plus)

Considering that the new wave doesn't really suit me, this movie actually got me quite a bit with how kind, beautiful, pleasant, comedic, and dramatic it is at the same time, and it has quite good characters that appear very natural. It is given by the documentary style that was used, as well as the real time that unfolds before you. The film manages to not be boring without any problems.

()

Annonces