Réalisation:

Mark HartleyScénario:

Mark HartleyMusique:

Jamie BlanksActeurs·trices:

Dolph Lundgren, Molly Ringwald, Bo Derek, Marina Sirtis, Olivia d'Abo, Robert Forster, Richard Chamberlain, Elliott Gould, Mimi Rogers (plus)VOD (1)

Résumés(1)

From acclaimed filmmaker Mark Hartley, Electric Boogaloo takes us on a hilarious thrill ride through the masterworks of Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, two movie-obsessed immigrant cousins who gate-crashed Hollywood's party, ran an indie studio that became the synonym for schlock, and nearly took over the industry in the process! From 1979 to 1989 their studio, Cannon Films, churned out more than 120 films featuring ninjas, nudity, wooden action heroes, threadbare plots, unintentional humour and accidental moments of genius. These cousins of chaos produced a breath-taking cavalcade of hits and misses, made movies based on posters, sold others they hadn't even made (or written!), released a sequel before the original film, botched plots, bounced cheques and burned careers – and in doing so changed the way movies were made and marketed. This is a one-of-a-kind story about two-of-a-kind men who – for better or for worse – changed the film industry forever. (IFF Bratislava)

(plus)Critiques (2)

Though this time Hartley chose a seemingly more cohesive subject (compared to the multi-layered and genre-diverse Australian and Philippine productions), his treatise on Cannon Films paradoxically comes across as the least well-made of his documentaries. The problem consists in the inherent weakness of Hartley’s method, as he lets the interviewees say everything and then composes the intended narrative by editing their statements. Unlike documentaries that combine testimonies with historical commentary to provide direction and a counterpoint, the success of Hartley’s films depends on a well-chosen set of speakers to achieve a good result. This method reached its ideal form in Hartley’s first and, with minor reservations, second documentaries, as he managed to strike a balance between informativeness and entertainment. This time, however, both of these aspects are significantly lacking. There is also the obvious lack of a Tarantino- or Landis-like personality who could comment on the history or stylistic elements in an entertaining way. Furthermore, Hartley abandoned the division of the film into thematic chapters, thus turning the uninterrupted stream of statements into a chaotic jumble without a clear direction. The unifying line should have been the chronological history of the company and its top representatives, which is not only constantly sidelined, but also has significant gaps. The most glaring shortcoming, however, is the absence of a number of the people who were involved, particularly the Golan-Globus duo themselves. Of course, Hartley attempted to engage them, but they – characteristically of their approach to films and their own image – declined to participate and promptly produced their own documentary, The Go-Go Boys: The Inside Story of Cannon Films. As a result, Hartley’s film shows only one side of the coin, namely the more critical and toxic side featuring offended starlets, slanderers, grumblers mocking various films and studio heads denigrating the quality of the films that had once earned them more-than-satisfying sums thanks to their distribution deals with Cannon. For the other side of the coin, represented by Golan’s and Globus’s own interpretation and radiating Eli Roth’s fannish enthusiasm, it is necessary to watch the aforementioned competing documentary. Though Hartley’s film itself hints at key specific aspects of Cannon Films and its business strategy (the pre-sales model) and creative approach (Golan’s enthusiasm and lack of good judgment), in most cases it unfortunately only scratches the surface, beneath which lies more than just a fascinating behind-the-scenes view of the Hollywood industry over the course of a decade.

()

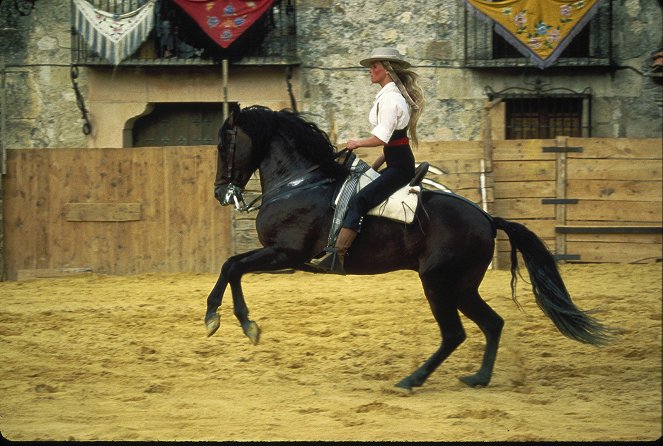

For some, the children of Cannon Films are a synonym of bad taste, others can't have enough of them, I myself stand on the fence between the two opposites. This documentary focuses mainly on the era of the two main bosses, Israeli friends Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus. It shows the cheap beginnings (Schizoid, X-Ray, House of the Long Shadows, the charmingly bad "worst musical of all time" The Apple), the flirtations with Asian themes (Nero's Enter the Ninja, the sequel Revenge of the Ninja, Ninja III: The Domination), genre fusions (Hercules, America 3000, Hooper's overwrought Lifeforce), sparse attempts at art (Zeffirelli's Othello, Sahara, where Golan was convinced to Oscar for Brooke Shields, lol, Konchalovsky's very critically successful Runaway Train) and rides on the popularity of break-dance (the hellishly bad Breakin'2: Electric Boogaloo, Beat Street). There's a nice explanation of the studio's efforts to "woo" acting stars so that the viewer identifies a particular face with Cannon Films. So, they talked Chuck Norris into producing his most trashy flicks of the 1980s, starting with Invasion U.S.A., Delta Force and the Missing in Action series, discovered Dudikoff (American Ninja) and confirmed the popularity of Van Damme (Cyborg), high-fived a fading Bronson (four sequels to the cult-classic Death Wish) and brought the world the popular sex symbol Sylvia Kristel (Emmanuelle one to a million). They tried to ride the wave of popularity of the Indiana Jones movies, so they farted out three (bellow) average adventure flicks with Allan Quatermain. It was commendable, however, that they occasionally lent a helping hand to progressive or somehow clever directors, so I was very surprised by their production of Barfly, about Charles Bukowski, by Barbet Schroeder, or financed Tobe Hooper's work at the time (Invaders from Mars, and the flop Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2). The last quarter of the documentary goes into a deeper analysis of why Cannon went bankrupt. While other comparably sized studios were producing 5 to 7 films a year, Cannon was producing 50 or more. This greed gradually caught up with them, and the final nail in the coffin was the costly flops Over the Top (Stallone's dull tale about an arm wrestler) and especially Lundgren's overblown Masters of the Universe and the awful Superman IV: The Quest for Peace. The financial bubble burst, longtime pals Golan and Globus went their separate ways, and Cannon ended up in debt. Not that I feel sorry for them, but I can't deny them the significant part they had in shaping the aesthetic and creation of 80s pop culture, whatever we think of it.

()

Photos (19)

Photo © Ascot Elite Home Entertainment

Annonces