Réalisation:

Lena DunhamScénario:

Lena DunhamPhotographie:

Jody Lee LipesMusique:

Teddy BlanksActeurs·trices:

Lena Dunham, David Call, Merritt Wever, Amy Seimetz, Alex Karpovsky, Jemima Kirke, Jody Lee Lipes, Alex Ross Perry, Lance Edmands, Nick Bentgen (plus)Résumés(1)

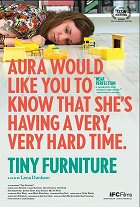

Aura revient auprès de ses parents à Tribeca, sa ville natale, après l'échec d'une relation sentimentale et de ses études cinématographiques. Sans savoir quoi faire, elle prend un travail de serveuse dans un restaurant, entretient des relations bancales avec des hommes égocentriques, et tente bien que mal de se définir. (texte officiel du distributeur)

(plus)Critiques (1)

A comedy of embarrassment. Aura attempts to establish a dialogue with a home that she no longer understands, but which she cannot exist without. She doesn’t know how to set down roots in the unexplored world of people who have graduated from university. She needs to know that she belongs somewhere and that somebody wants her. Throughout the film, she tries to reclaim her position as a daughter, to get permission from her mother to sleep in her bed, to be her child again. At least for a moment. This is not only a manifestation of fear of responsibility and emotional insecurity on her part, but also of dependency, her inability to look past her own problems and see those of others, and the need for someone to guide her. If I can judge from my experience as a viewer, for a person of the same age and with the same starting position as Aura, Tiny Furniture is simultaneously pleasant and annoying. It’s pleasant because it is easy to settle into its microcosm of awkward silences, timidity and impropriety, and it’s annoying because it confronts her with her own immaturity, parasitising on others’ success and constantly looking for ways to make her life easier. But what are we actually entitled to at our age and in our position? Why do we consider it unacceptable to be lonely, without power and without money? The unteachable, negative and self-absorbed characters are both role models and cautionary examples. Lena Dunham shows the naked truth (though still not as “naked” as in the later Girls) without moralising, but at the same time without any romcom refinement. She shows real people whose contradictory characters cannot be judged and condemned in a single sentence. The camerawork is equally expressive and even more ambiguous, as it succeeds in capturing the characters’ mood and situation through the composition of the shots and the involvement of the mise-en-scène (the coldly elegant framing of the apartment as several aseptic cubicles with none of the warmth of home). If you don’t feel embarrassed because of the characters, the environment in which they live will reliably give you the feeling of impropriety. 85%

()