Réalisation:

Matthew BrightScénario:

Matthew BrightPhotographie:

John ThomasMusique:

Danny ElfmanActeurs·trices:

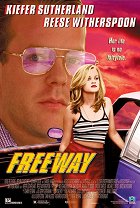

Kiefer Sutherland, Reese Witherspoon, Wolfgang Bodison, Dan Hedaya, Amanda Plummer, Brooke Shields, Michael T. Weiss, Bokeem Woodbine (plus)VOD (1)

Résumés(1)

Vanessa (Reese Witherspoon), 16 ans, est une jolie fille issue de la jungle urbaine d'Amérique. Elle évolue dans un monde absurde : une mère toxico, Ramona (Amanda Plummer), qui se prostitue pour acheter sa dose de crack et Larry (Michael T. Weiss), son beau-père, qui essaie de la peloter. Après une descente de police musclée où sa mère et son beau-père sont arrêtés, Vanessa décide de s'enfuir pour ne pas être, une fois de plus, placée dans une famille d'accueil. Tel le Petit Chaperon rouge, elle s'en va retrouver sa grand-mère qui vit dans une caravane à quelques centaines kilomètres de là. En chemin, elle rencontre Bob Wolverton (Kiefer Sutherland) psychologue pour enfants le jour et grand méchant loup la nuit. (Metropolitan FilmExport)

(plus)Critiques (1)

Matthew Bright is either a cursed genius for whom there was no place in Hollywood, an irrational idiot, or just a filmmaking punk who has pissed on the classic standards of craftsmanship from on high. His filmography swings between the poles of the iconic underground Forbidden Zone and the star-studded melodrama Tiptoes. Freeway stands somewhere in the middle and shows Bright to be a diamond in the rough and subversive anarchist in equal measure. His directorial debut, which in its time was featured in the main section at Sundance, was produced under the auspices of Oliver Stone, who at the time was immersed in deranged visions of the outer fringes of America with projects like Natural Born Killers and U Turn. The crew was composed of a mix of dime-store fantasists reared by Roger Corman and renowned names, with Maysie Hoy at the fore, brought up by Robert Altman and Bright’s old buddy Danny Elfman. Despite the stellar cast, the film proudly shows off its punk pedigree with long, uninterrupted shots and exalted acting performances that evoke underground classics such as those of Christoph Schlingensief. After all, Freeway shares with Schlingensief’s projects not only an overarching principle of production, which we can summarise as “quickly, cheaply and furiously”, but also the basic concept of hysterically subversive appropriation of mainstream motifs and their emancipatory transference to a fringe environment, in this case the world of delinquents, streetwalkers and junkies. Bright’s paraphrase of Little Red Riding Hood manoeuvres between exploitation exuberance and soap-opera theatricality, while serving up an angry fairy tale that, with a feminist touch, takes into account traditional sexism and privileged arrogance. The journey of this Little Red Riding Hood with a lengthy rap sheet from a bleak home on the periphery, saturated with sexual abuse, drugs and social misery, to her grandmother’s home in a trailer park takes a lot of convoluted turns, including a reform school, that classic backdrop of movies about juvenile delinquents. But as in the story by the Brothers Grimm, the encounter with the wolf brings not only danger, but also an awakening and awareness of one’s own worth, not only in terms of how much to charge for a back-alley blowjob.

()