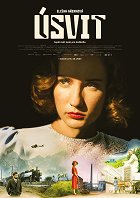

Réalisation:

Matěj ChlupáčekScénario:

Miro ŠifraPhotographie:

Martin DoubaMusique:

Simon GoffActeurs·trices:

Eliška Křenková, Miloslav König, Milan Ondrík, Marián Mitaš, Luboš Veselý, Martha Issová, Ladislav Hampl, Ján Jackuliak, Anton Šulík ml. (plus)Résumés(1)

In the 1930s, a pregnant doctor must navigate a web of superstition and prejudice while seeking the truth about a shocking find at her husband's factory. (Netflix)

Vidéo (4)

Critiques (8)

Pour un réalisateur de 29 ans, ce film est une entreprise extrêmement ambitieuse, avec des moments intimistes et forts sur un sujet inédit, délicat sur le plan social. Úsvit fonctionne à merveille, avec son message intemporel sur l’incurable étroitesse d’esprit de la société, ses préjugés et son intolérance à l’égard de tout ce qui est différent. Cependant, le film ne conviendra pas à tout le monde du fait de la juxtaposition des différentes intrigues secondaires (la relation problématique entre la protagoniste et son mari carriériste, la figure troublante d’un officier du contre-espionnage) ou parce qu’il se déroule dans un microcosme industriel à la « Bata ». Pourtant, c’est cet univers qui ajoute à l’attrait du film pour le public et à l’ancrage historique du récit, pour mieux en souligner l’idée. Et avec des décors de studio joliment stylisés au premier plan de la chaîne de montagne des Hautes Tatras, cela ajoute également au caractère esthétique de cette parabole artistique. L’œuvre n’est certes pas complètement aboutie dans tous ses détails, mais il s’agit sans aucun doute d’un film que la plupart des cinéastes tchèques n’oseraient pas réaliser. Matěj Chlupáček est vraiment dans un autre monde et si dans les dix prochaines années il parcourt le même chemin qu’entre Bez doteku et Úsvit, le public sera debout à Cannes et à Venise pour y applaudir son troisième long-métrage. [Festival du film de Karlovy Vary]

()

Le niveau technique est excellent, tout comme le choix de l'époque et du milieu et la scénographie associée ou encore l'utilisation de bâtiments miniatures et d'effets qui incorporent des personnages vivants. Même le maquillage prothétique sur le visage de Ladislav Hampl est plutôt balèze. Par contre, l'histoire, les thèmes associés et les personnages fonctionnent moins bien et semblent parfois aussi lourds que le pitoyable titre anglais We Have Never Been Modern. J'ai un problème avec certains aspects moraux du film, qui soit sont présentés comme vierges de problèmes, soit sont tout simplement glissés sous le tapis. Cependant, il s'agit toujours de l'une des œuvres thématiquement intéressantes de la cinématographie tchèque de cette année, bien que selon moi, elle suive un peu l'adage « au royaume des aveugles, les borgnes sont rois ». [KVIFF 2022]

()

Someone filmed a series that was decided to be only a film in post-production. Actually, I'm a bit disappointed not to rate it higher because its crafty creative ambitions are easily justifiable on a European scale, but the development of the plot on multiple fronts only leads to a satisfying conclusion in one case (the marital dispute on the staircase, where the perception of the characters is completely turned around, is a screenplay gem, no debate about it), while each of the fronts deserved to be explored much more. Thus, it remains a cheap crime story from a dime-store detective novel, the building of capitalism on the scale of a newspaper article, and a counter-diversion action from a wet dream of a novice spy. However, the "modern" theme of the film holds up, a bit clumsily but effectively and sensitively, in retro attire. 3 and ½.

()

It’s a shame that of all the topics raised in We Have Never Been Modern (the Czech industrialist Baťa’s utopia/dystopia, tolerance, the political grudges of the First Republic, women’s standing in society), the film doesn’t really develop any of them and rather merely presents them. Similarly, it awkwardly shifts between the genre layers of an otherwise appealingly constructed story. The film seems as neglected as the female protagonist, whose suspicious “rightness” becomes problematic only in the end. The powerful dilemma is resolved very carefully in the comfort zone of Baťa-style modernism. We Have Never Been Modern proceeds with caution and is a bit clumsy in explaining things (the doctor’s animated lecture about hermaphroditism was the only WTF moment). In spite of that, however, it is one of the most interesting films that Czech cinema has generated in recent years. The attempt to be different and to make a masterfully crafted period piece is quite obvious, but I couldn’t shake off the impression that the film occasionally couldn’t get out of its own way in its effort to not go down the well-trodden paths.

()

I would very roughly describe We Have Never Been Modern as a period detective melodrama, but it cannot fulfil any of the characteristics of that genre, because it is a film with a fluid genre identity. This corresponds to one of the film’s central themes, which is the inconstancy of gender identities and social roles, as well as the impossibility of incorporating certain facts into familiar frameworks and categories. Though the story takes place in the 1930s, its strength lies in something that isn’t often seen in Czech period dramas – it clearly relates to problems that are relevant to the present. The essence of the film is not the black-and-white struggle against Nazism or Communism, but rather the current feeling of anxiety caused by a society that is only outwardly modern while it allows the restriction of human rights and individuality under the pretext of rationalisation, automation, security, economic growth and building a better tomorrow. If we wanted to identify a villain in the narrative, it’s not the state or the group representing a particular ideology, but the company and its capitalist logic based on thoughtless expansion and exploitation. This is connected with the key theme of the clash between tradition and modernity, where it is again shown that even though we have state-of-the-art production processes, that doesn’t help us much if there isn’t any progress in the thinking of people who cling to certain prejudices and stereotypes and who have the need to determine for others what is normal and to tell people how they are supposed to live. The consequence of that is that this emerging better world is accessible only to those who submit to the given norms and fall in line. The intersex character is a threat to the given order and rationality. In how the others treat her, we see an example of the reactions that we can still encounter today. Ridicule, denial and elimination, as well as the effort to ascertain the necessary facts and to understand exactly what it means not to unambiguously be either a man or a woman from the biological perspective. Together with how the reaction of the female protagonist played by Eliška Křenková evolves, the genre of the film also evolves. Mysterious crime thriller, science film, melodrama, social drama… Though I understand that the changes in genre and making the otherwise imperceptible style visible (the animated interlude, Helena’s glances into the camera, the pointing out of how every retelling of events is also an interpretation over which the participants in those events have no control) may be unsettling for some, they are based on what the film thematises, i.e. rebelling against norms, being uncategorisable, deviating from convention. This brings both anxiety and an awakening (or a new perspective on the matter), which is true both for both Saša and Helena, who realises who or what is important to her in life. Just as the film is ambiguous in terms of genre, the characters are not black-and-white. The complex female protagonist, again something quite rare in Czech cinema, is portrayed superbly by Eliška Křenková. Her Helena convincingly transitions between bitterly commenting on the events happening around her and displays of sensitivity, while also imposing on others her idea of what she thinks is right. The clash of different worlds and attitudes is not conveyed only in the scenography or the work with colours, but also in the contrasting acting performance (the informal Křenková vs. the deliberately affected König), as well as in the use of anachronisms (for example, the fact that the characters use modern language), which highlights the parallels with today. Whereas, in the end, Helena looks to the future with legitimate concerns (as we should too), the future of Czech audio-visual art appears to be somewhat more promising with creators such as Šifra, Douba and Chlupáček. Their We Have Never Been Modern is in fact a modern, refreshing film with a well-developed concept that I believe can spur a discussion of issues that should be addressed today.

()

(moins)

(plus)

Annonces