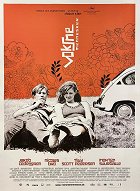

Réalisation:

Dagur KáriPhotographie:

Manuel Alberto ClaroMusique:

SlowblowActeurs·trices:

Jakob Cedergren, Nicolas Bro, Tilly Scott Pedersen, Morten Suurballe, Bodil Jørgensen, Nicolaj Kopernikus, Anders Hove, Kristian Halken (plus)Résumés(1)

Daniel est un artiste grapheur qui gagne sa vie en inscrivant sur les murs les déclarations d'amour qu'on lui commande. Charmant et totalement irresponsable, son mode de vie est cependant complètement marginal. Tout le monde est à ses trousses, à commencer par le propriétaire de son bungalow. Un jour, il tombe amoureux de France. (texte officiel du distributeur)

(plus)Critiques (1)

*SPOILERS* The key to why Kári chose seemingly distant and only frame-related stories of the judge and the "association" may be in one seemingly unimportant detail, which the director "mysteriously" emphasized. It is a double scene with punch-outs of paper from a hole punch, which the desperate judge first sprinkles on himself, and a little further on, in the same activity, the outsider Daniel marks them as holes (after which he is corrected that these are punch-outs, that the holes are in the paper). This "psychoanalytic" detail quite faithfully captures the two opposing characters: the judge has everything, yet he still lacks something, something that uproots him and drives him into desperate solitude. Daniel has nothing and desires nothing, he deals with the system (the great other) with a complete passivity that has nothing to do with revolt, and much more with the misunderstanding that there is any "symbolic order" to which I am subordinate at all. Daniel's indifference to the object of desire and "rift" is, in fact, what allows him to be happy (his story conspicuously resembles the post-hippie poetics of Copenhagen's Cristiania district – it's no longer about rebellion, just a slightly shy parallel existence "next to" the great other, with the need to accept at least the general rules of responsibility). On the other hand, the judge, the lawyer and the representative of the order, is condemned to dissatisfaction and to spontaneous disappearance – there is no place for him either "in" or "next" to the system. Grown-up People is not so much about revolt as it is about the possibility of coexisting – I like its naïve silent ending in many ways. Even if he answers yes, he leaves the door ajar. At its core, it's another praise for the simpletons, but thanks to an excellent second line with a man who's disappeared, it keeps its feet on the ground and, unlike its protagonist, doesn't lose touch with reality.

()