Critiques (935)

Hunger Games - La révolte : Partie 2 (2015)

It had to end with the cat. I understand that the filmmakers had to stay true to the book’s ending, but the impression that the film leaves is in conflict with more than just the transformation that Katniss underwent in the two preceding instalments (the mention of nightmares as an indication of PTSD is rather unconvincing in light of the kitschy stylisation of the scene). At the same time, it deadens the whole trilogy’s “emancipatory” potential by passing off the dumbest gender stereotype as the ideal state. Eastwood similarly cut the recent American Sniper off at the knees in its final minutes. Otherwise, Mockingjay – Part 2 is a generally satisfying effort to make a YA blockbuster that rejects certain genre conventions (the unspectacular beginning, the most epic action taking place long before the atypically intimate ending, the blurred line between good and evil) and even has something to say to adults (war propaganda, the demise of the old world, the overlaying of real memories with media representations). Like Mockingjay – Part 1, the film begins with an unusually dark and bombastic scene that sets the course of the narrative. Katniss must regain (literally and figuratively) the voice that she lost in the previous instalment. Through most of the film, however, her control over the situation is not as great as she imagines it to be or as is indicated by her heroic framing (at the centre in order to dominate the whole shot while towering over the other characters) and the frequent shots of her face filling the entire screen. Katniss’s journey of personal revenge is for the most part a propaganda spectacle directed from above for the masses, essentially another edition of the Hunger Games, with the ruins of the Capitol serving as the new arena. The illusion of freedom of choice and the fight for a just cause isn’t destroyed as thoroughly as the previous instalment promised, but the film is still a likably unique incentive to think about the mass production of pop-culture rebels who fail to grasp the idea that they are not fighting against the system, but within it. 75%

Hunger Games - La révolte : Partie 1 (2014)

“Order shall be restored.” The next to last instalment of The Hunger Games is perhaps not the most elegant example of Hollywood storytelling – in the end, the whole film is an unfulfilled promise of something tremendous – but in terms of media self-reflection, it offers enough impetus to keep you thinking for many days after seeing it. Haunted by nightmares, Katniss gains inner peace not by finding a kindred spirit and actively taking control of the situation, but by accepting the media role that has been created for her. Using dresses, computer effects and fighting words, she transforms into an effective tool of revolution, a player in an artificially constructed reality, which she herself gradually stops perceiving as something alien, separate from the real world. She gradually accepts her role and the vocabulary of her creators and adapts her behaviour to the (omni)present camera and the interests of the revolution (“Don't shoot here. I can't help them”). Her position as a mere symbolic object is clear from the situations in which she passively finds herself and from the way the other characters relate to her (even in her presence, they speak of her in the third person and are primarily concerned with making her look good in promotional videos). Playing on emotions, the narrative is tailored to her spontaneous decisions, essentially making it impossible for her to exit the story. What she doesn’t realise is that her story mirrors that of Peeta, that she herself has become a cat dully chasing the light (perhaps a needlessly conspicuous metaphor, but also a quite clear indication that it is a mistake to approach the film as a standard genre flick). The making of the rebel and the selling of the revolution happens in parallel on two levels (in-text and outside of the text) and it’s as if the film gives us a look behind the scenes of its own creation. After a gripping action scene in an otherwise unusually unspectacular, slow and disturbingly quiet film, the same shots of the attack on the rebel hospital are repositioned in the context of a propagandistic “weekly” whose purpose is to manipulate the masses, just as we were manipulated (captivated by the spectacle) a moment before. The camera “journalistically” follows Katniss even in scenes where she is not filmed in the diegetic space. The blending of shooting styles leads to the further blurring of the line between propaganda for the people of Panem and for us. We can thus see the film’s ending, warning against the authentic with the artificially produced television broadcast intended to cover up what is happening in reality in the meantime, as the ultimate act of insincerity perpetrated by an industry built on a similar distortion of reality, or accept it as an ingenious rebellion carried out within the confines of a major-studio Hollywood narrative. However, the filmmakers could not have taken the liberty of launching a rebellion if it didn’t involve an adaptation of a bestseller capitalising on the demand for stories of defiance against the old order and whose multimillion-dollar box-office receipts are guaranteed in advance. 80%

Strictly Criminal (2015)

In a story with prominent religious overtones, Depp’s Boston bloodsucker personifies an irresistibly seductive evil and, thanks to his charisma, wins you over to his side more easily than the boring good. Like the ambitious but so far unsuccessful Connolly. However, it cannot be said that the FBI agent is the story’s protagonist through whose eyes we follow the plot and with whom we are supposed to identify. The camera keeps the same distance from him as it does from the other characters, whose inner world we also have no access to (in the form of flashbacks or internal monologues, for example) and we see them only from a distance, more as noteworthy objects to observe than as participants in the narrative. An exception, when we see the actors’ faces in close-up, is the scenes of violence. The terrified expressions of those who witness Bulger’s sadism illustrates their awareness that they could easily become his next victims. We also see the faces of the victims, who are exposed to psychological and physical violence together with their wives and are the only characters with whom we can sympathise. They are characteristically the most powerless characters, who cannot influence anything and cannot do anything to prepare themselves for the approaching evil except read The Exorcist (like Connolly’s wife). The film’s restrained visual style, based on very slow camera movements, static wide-angle shots and dim lighting, corresponds to the attempt at a reserved procedural reconstruction of why the alliance between the FBI and Bulger resulted in so many deaths and contributes to the creepingly slow pace of the narrative. In approaching the actual events in a factual, descriptive manner in the style of a documentary, Black Mass keeps an aloof distance from its characters, offers fragments that we have to piece together ourselves instead of a fully formed narrative, and frames the world of organised crime without attempting to present an engaging spectacle. Conversely, it doesn’t offer the expected pleasure of a genre flick and requires more cooperation from the viewer than you would expect from a Johnny Depp film, but it will more likely stay with you longer than movies that cater to viewers and don’t place major demands on them. 75%

1941 (1979)

Spielberg’s boorish variation on Dr. Strangelove (to which Slim Pickens’s character makes a direct reference) is similarly over-the-top as some of the overly ambitious ensemble war movies of the 1960s and ’70s (A Bridge Too Far, Tora! Tora! Tora!, The Longest Day). Compared to those, however, 1941 is well aware of its bombast and, starting with the opening scene in which it parodies Jaws from only four years previous, it makes it clear that the screenwriters and the director adhered to the motto “anything goes”. If “immoderation” remains the keyword throughout the film, it’s in an attempt to revive the anarchic legacy of slapstick and, at the same time, to present a hyperbolised version of what Hollywood usually does with historical facts (in line with the film’s self-deprecating humour, Hollywood is the main target of the Japanese submarine). 1941 is an assuredly false reconstruction of events that occurred (or didn’t occur) in L.A. in February 1942. While the general is watching Dumbo at the cinema, the soldiers are chasing girls and punching each other in the mouth instead of going after the enemy. As evidenced by contemporary reviews, American society was not prepared for this disparaging – “Italian”, if you like – depiction of war. However, disrespect for historical facts is not the film’s main problem (on the contrary, I was pleasantly surprised that Spielberg used American patriotism as a basis for pure farce). What’s more bothersome is the madcap chaining together of variously destructive misunderstandings, which gets old rather quickly due to its monotony, despite the skilful directing, decent tricks and outstanding music (which both ridicules and pays tribute to the soundtracks of serious war movies). There are no characters, let alone a plot line, that would unify the narrative, many of the sketches are drawn out and gratuitous, and overall the film is far less funny than it should/could be on paper. Despite that, it is a remarkable experience to watch 1941 as, for example, an imperfect prototype of current blockbusters, which also pile one attraction on top of another. Spielberg was (unsurprisingly) able to bring the poetics of animated slapstick (and many video games today) into a feature film more successfully only in the animated Tintin, in which the continuous action chaos seems much more organised. 60%

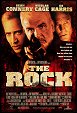

Rock (1996)

“Personally, I think you're a fucking idiot.” When I was ten, I thought The Rock was the best action movie ever made. With the passage of many years, I still wouldn’t change my opinion. There are different reasons for why I admire Bay’s (and Bruckheimer’s and Simpson’s) masterpiece. He created a world in which everything is subordinated to the maximum action experience. The characters’ decisions don’t have to make much sense (and they don’t) – the main thing is that their actions look good (of course there is the characteristic circling around the actor from above) and generate more action situations. Despite its ambitious runtime and relatively long but later fully utilised exposition (we don’t get to Alcatraz until after an hour), The Rock is gripping from start to finish thanks to the actions happening in parallel, the deadline set immediately at the beginning and the continuous reminders of it, and the relentlessly driving soundtrack that transforms the film into a ready-made Zimmerfest. We don’t have a chance to catch our breath, thanks especially to the film’s brilliant rhythmisation. At first every ten minutes and then at even shorter intervals toward the end, a new obstacle/character brings about a key decision or the situation becomes more serious every. The diverse range of action scenes (car chases, shootouts, hand-to-hand combat) reveal new information and push the narrative forward. In addition to the horizontal forward movement, there is a vertical deepening of the bond between Goodspeed and Mason (the dynamics of their relationship become one of the drivers of the narrative in the second half) and of our knowledge of the characters and their motivations (Ed Harris definitely does not play a one-dimensional supervillain; on the contrary, the film’s first shots suggest that he could be the hero). The film, which thematises paternal responsibility in the second plan and offers a distinctive way of coming to terms with the trauma of Vietnam, continuously changes and develops, never ceasing to keep us in suspense and to surprise us, and never letting up for even a moment. Connery throw out one-liners like crazy, expensive cars are gleefully demolished and the bad guys are dispatched in inventive ways. The humour and ingenuity of the polished screenplay (in which Aaron Sorkin, among many others, had a hand) don’t turn The Rock into either light entertainment or an overly clever, self-reflexive deconstruction of the genre. Both of these aspects mainly help to humanise and better flesh out the main duo (in contrast to the deadly seriousness of the soldiers and the people running the FBI). Behind all of the spectacular explosions, daring heroic deeds and insane plans to exterminate humanity, we perceive throughout the film a believable human element, thanks to which we never lose interest in what’s happening and what comes next. In short, The Rock is a perfectly balanced mix of Bond, western and buddy movie. 95%

The 50 Year Argument (2014)

Intellectuals for themselves. Martin Scorsese has written another love letter (with the assistance of editor David Tedeschi). This time the addressee is not Elia Kazan or any other American or Italian director, but the editorial board of the The New York Review of Books. It is not an attempt to uncover the political-economic context in which the magazine was and is published, but rather to express admiration for one particular periodical and for serious critical writing as such. Instead of a linear overview of events, following the initial summary of the origins of the NYRB, the documentary’s creators jump from one sensational article to the next within the framework of vaguely defined thematic blocks. Where possible, opposing perspectives on contemporary events are presented not only through the authors’ readings and commentary, but also through images. Thanks to archival materials from various street riots, the film is thus made up of more than just talking heads, though they are still given the most space. Neither formalistically nor in terms of content, the film is not comparably as confrontational as the lively discussions that some of the texts provoked. Instead of stirring up controversy, The 50 Year Argument only recapitulates what happened from one (liberal) perspective. For NYRB readers, this will be 97 minutes spent in the pleasant company of their favourite writers. Viewers who are unfamiliar with New York’s intellectual scene will nod in agreement a few times and appreciate the fact that someone has made a documentary about intelligent people who write unpopular opinions for a living, but they are unlikely to become NYRB subscribers. The 50 Year Argument is an elitist affair comparable to Public Speaking, Scorsese’s portrait of Fran Lebowitz, which also doesn’t make much of an effort to accommodate people riding a different wave of thought. 65%

Koza (2015)

The restrained camerawork serves as a safeguard against the kind of exploitation of poverty that the makers of other social dramas indulge in. Furthermore, the images of destitution in which Goat lives are never underscored with histrionic music. Besides terse lines like “Don’t chew, eat”, we hear only the amplified sounds of the setting. The best thing is that the reluctance to make an impressive spectacle out of the story of a boxer returning to the ring is apparent in the filming of the matches as whole images, with the camera positioned far from the boxers. Unlike films such as Raging Bull, in which we find ourselves directly in the ring, here the camera passively remains standing at a distance, without gradually approaching the boxers. ___ Sometimes more attention is paid to the spectators, who obviously live in better conditions than Goat, than to the match itself. This involves another departure from the conventions of boxing dramas. The body here is not a continuously perfected fighting machine, but an object of exploitation worth a few hundred euros. Self-destruction for other people’s money is framed as an activity with as little dignity as collecting old iron waste, thus indirectly underscoring Goats social exclusion. His isolation, apparent also in the fact that we usually see him alone in the given shot, is intensified in a different language setting. He can barely count to five in English, let alone carry on a meaningful conversation. ___ Unlike in The Way Out, Goat does not fight against the system and his Romani origin is not directly thematised. He is out of sync with the rest of society and the world of boxing. He lacks the strength, cunning and ruthlessness of others. Thanks to that, this is an existential story of a man who has somehow learned to survive in the given conditions (for example, by collecting and selling iron), but at the same time has been out of training for so long that he has no chance to catch up with the world around him. He is always a few metres behind: more than once we see him running after a moving car, once he misses a ferry and has to wait for the next one.___ The illusion that we are watching real, non-staged situations is only occasionally broken by scenes in which Baláž tries to convey what the screenplay prescribes. His inability to embody the prescribed role reveals the limits of the method of blurring the line between documentary and fictional films. Ostrochovský, however, was apparently aware of Baláž’s limitations as an actor and instead lets the images do as much of the talking as possible. ___ As intentionally monotonous as the “match-car ride/training-fight” structure is (as is the boxing itself), Goat manages to hold the viewer’s attention by revealing information from the protagonist’s past at approximately ten-minute intervals and pointing out Baláž’s continuously deteriorating health. The protagonist is not introduced by his titular nickname until nearly half an hour into the film, when he laconically utters, “They call me Goat.” From terse conversations, we similarly learn only gradually and seemingly inadvertently that Nikolka is Goat’s stepdaughter (and he would therefore like to have a child of his own) and that he was raised by his grandmother who fed him goat’s milk (from which he got his nickname). At the same time, however, the compact structure doesn’t cause the film to seem like a carefully shaped construct that is merely fulfilling a preconceived plan. The situations correspond to the characterisation of the characters and arise naturally from external conditions, which is also aided by the presence of seemingly random events that are not further elaborated upon in the narrative (the ride and robbery of the hitchhiker). ___ Goat is a film of satisfying stylistic purity that doesn’t venture into uncharted territory and is not breathtaking in its message or execution, but without exaggeration, it can be measured against the festival films of other European countries, which in the end is the greatest victory for both Goat the film and (for a long time) Goat the boxer. 65%

L'homme en plus (2001)

The double life of Antonio. In his debut, Sorrentino limbers up with the stories of two men who live different yet identical lives, told in parallel. Similarly as in Kieslowski’s mystical drama, the life stories of the two characters are strangely interconnected – one of them encourages the other to actively take control of his passively lived everyday life. Emptiness, loneliness and abandonment characterise the existence of both men, two endlessly defeated players who vainly search for a suitable (playing) position. Sorrentino shares with Scorsese not only an interest in frustrated men whose (self-)destructive behaviour stems from their inability to fulfil their ambitions (the climax is roughly reminiscent of Taxi Driver), but also stylistic mastery. He doesn’t need to obviously quote his more famous American inspiration (breezing into the club à la Goodfellas) in order for us to understand that he, like Scorsese, dislikes static compositions, traditional camera angles and hackneyed combinations of music and images. The soundtrack, which not only creates incongruous audio-visual combinations, but also directly connects the two protagonists, is one of the strongest components of the film, which otherwise undeniably has problems with pacing and with the inconstancy of the utilised fantastical exaggeration. At the beginning of his career, Sorrentino was not yet skilful enough in stylistic contamination to elegantly combine Scorsese with Fellini. In his later films, he has been able to better tame the many artistic influences on his work and, mainly, he doesn’t try to use every decent idea at all costs. Nevertheless, it would be nice if more debuts excelled with comparable craftsmanship. 75%

Sicario (2015)

Sicario is an intense action crime-thriller that betrays both the protagonist and the viewer. Most of the time, the film comes across as a surgically precise procedural in the mould of Zero Dark Thirty, giving us enough information and paying close attention to the preparation and execution of individual scenes of action that lead to more action, rather than focusing on the relationships between the characters. In fact, we spend almost the whole time watching a revenge movie along the lines of Ford’s The Searchers, but it doesn’t let us know who is seeking revenge for what (or if anyone is seeking revenge at all). The supply of information is severely limited (both of the brutal interrogations, where in a bit of unrestricted narration we abandon the protagonist’s perspective for a moment, end before we learn anything important), putting us in the same position as Kate, who finds herself in an unfamiliar environment controlled exclusively by men. Throughout the film, she tries in vain to understand how – in Javier’s words – “watches work” and to see beneath the surface instead of just watching time pass. Just as in the uncompromising prologue, when she barely dodges a shotgun blast, thanks to which she learns what’s hidden behind the wall, she’s mostly lucky and has zero control over what happens around her throughout the rest of the film. The protagonist’s limited access to information corresponds to the shooting of some of the dialogue scenes in whole units, thus emphasising her vulnerability to the hostile world in which she finds herself. Sicario is primarily a clever, brilliantly rhythmised genre movie with some of the most impressive action scenes of the year (one of which, like the climax of Zero Dark Thirty, apparently took inspiration from video game). It shows us the disgustingness, opacity and danger of the war with the drug cartels particularly through stylistic choices and the structure of the narrative. If we were to approach it as a psychological probe or a complex portrait of the conditions on the US-Mexico border (à la Traffic), it probably wouldn’t hold up. The heightened attention paid to the Mexican police officer from the beginning serves the purely utilitarian purpose of reinforcing our emotional engagement (and ensuring a powerful final shot), rather than offering a fully formed view from the other side. The evil that the characters face here has a unique form similar to that in Michael Mann’s thrillers (whose work with sound design during shootouts is no less precise), whereas Sicario’s western iconography and uncompromising (and not the slightest bit cool) approach to violence are reminiscent of Sam Peckinpah’s films. In fact, the thematisation of the (much less distinct than before) boundary between civilisation and savagery, and the crossing and shifting of that boundary, makes Sicario one of the best Mexico-flavoured revisionist westerns since The Wild Bunch. 85%

Mon roi (2015)

At one point, Georgio exaggeratedly refers to himself as the king of the idiots. I would like to believe that this is how the director intends for us to perceive him for most of the film, i.e. not through the incorrigibly loving view of Tony, who never stops idealising her partner even after he has robbed her of her good mood, her nerves and all of her furniture. Whereas melodramas mostly try to convince us that true happiness consists in love until death do us part, the love in My King draws not only the best qualities out of people, but also their worst, which gradually prevail. Just as in real life, the central couple’s relationship turns into a war of egos and an exhausting cycle of breaking up and making up, sustained partly by faith (that things will be made right) and partly by fear (of being alone). In this respect, the film is as painfully truthful as in its unembellished depiction of arguments, drunkenness and the effort to walk off a broken knee. Due to its repetitiveness, however, this film packed with perceptively observed situations is as tiresome for the viewer as Giorgio and Tony’s relationship is for them. This time, even more than in Polisse, Maïwenn relies on charismatic actors who fully embody their roles and whose seemingly improvised dialogue, arguments and bedroom games are more or less adapted not only to the length of the individual scenes (exaggerated), but also to the dramaturgy of the film as a whole (relaxed). The attempt at authenticity, which is relatively successful with the exception of a few hysterical escapades, is undermined by the fact that the film – together with the protagonists – becomes increasingly unbearable and from a certain moment it does not even convey anything new, instead only blurring the protagonist’s displays of growing emotional instability (which conversely makes it highly melodramatic). Furthermore, I’m not sure whether or not the film is a warning against unintentionally falling in love (and relationships in general), but thanks to that, there is a decent chance that My King will appeal to both cynics and romantics. 70%